When it comes to the northern and southern lights, it’s tempting to assume that once the Sun passes solar maximum, the show is over. After all, solar maximum marks the most active period of the Sun’s roughly 11‑year cycle, when sunspots, solar flares, and coronal mass ejections (CMEs) are most frequent.

But according to space physicists, the years following the peak can still deliver plenty of excitement for aurora watchers.

A Space Physics Ph.D. student, night sky photographer, and self-confessed aurora fanatic. As a science communicator and educator, Vincent breaks down space weather for aurora lovers worldwide through his blog and social media channels.

To understand what aurora chasers might expect in 2026, we spoke with Vincent Ledvina , a Space Physics Ph.D. student at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, widely known online as “The Aurora Guy.” His research and outreach focus on how solar activity translates into geomagnetic storms and auroras here on Earth.

What’s Going on with the Sun in 2026?

As the Sun moves away from solar maximum and into the declining phase of its cycle, explosive events such as major solar flares and fast CMEs become less frequent overall. But that doesn’t mean geomagnetic activity disappears. Instead, the dominant drivers of space weather begin to shift.

One of the most important players in this phase of the solar cycle is something known as a coronal hole.

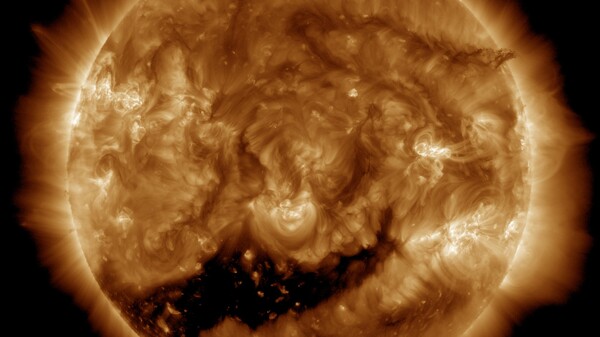

Coronal holes are regions where the Sun’s magnetic field is “open,” allowing solar plasma to escape more easily into space. “Because plasma can escape more easily there, the corona above them is less dense and cooler,” Ledvina explains. “That’s what makes these regions look dark in extreme ultraviolet imagery.”

While coronal holes exist throughout the solar cycle, they tend to become more prominent and influential after solar maximum. That change is tied to how the Sun’s magnetic field evolves over time.

“As the solar cycle progresses, the Sun’s magnetic fields do a full reversal,” says Ledvina. “At solar maximum, the magnetic field is very jumbled as it’s flipping. In the declining phase, the large‑scale magnetic field becomes more organized again.”

As active regions decay, their leftover magnetic fields can reorganize into large, stable patches that open up into coronal holes, sometimes stretching across the Sun’s equator.

Why Coronal Holes Matter for Auroras

Not all coronal holes are created equal when it comes to auroras on Earth. Some are better at producing space weather more likely to be Earth-directed; these are transequatorial coronal holes—those that extend across or sit near the Sun’s equator.

“Transequatorial coronal holes are most important for geoeffective space weather,” Ledvina explains, “since they send fast solar wind right at Earth, as opposed to the polar coronal holes, which are spitting out fast solar wind north and south of the Sun.”

They act like solar wind lighthouses.

Vincent Ledvina, Ph.D. student at the University of Alaska Fairbanks

The Aurora GuyThese low‑latitude coronal holes often act like long‑lasting solar wind sources. As the Sun rotates, the same coronal hole can repeatedly sweep Earth with high‑speed solar wind.

“From Earth’s perspective, this beam of fast solar wind washes over us once every 27 days or so, roughly how long it takes for the Sun to rotate once on its axis. They act like solar wind lighthouses,” explains Ledvina.

The geomagnetic storms produced by coronal holes are usually minor or moderate rather than extreme, often around G1 or G2 levels. Still, for aurora watchers—especially at higher latitudes—these storms can produce beautiful displays.

A More Predictable Kind of Space Weather

One upside of coronal‑hole‑driven activity is its repeatability. Because these features can persist for months, forecasters can look ahead using tools like NOAA’s 27‑day geomagnetic outlook.

However, Ledvina cautions aurora chasers against planning trips solely around these forecasts, as coronal holes can weaken, shift, or close up entirely, and not every high‑speed stream triggers a geomagnetic storm. Intriguing seasonal effects also come into play:

“The seasonality does change how effective some coronal holes are at Earth,” Ledvina notes, referring to the Russell–McPherron effect, which results in statistically higher geomagnetic activity around the equinoxes.

What About Big Storms?

While coronal holes dominate the declining phase, CMEs don’t disappear—and some research suggests that the most extreme geomagnetic storms may actually cluster later in the solar cycle.

“Extreme events are more common during the declining phase,” Ledvina says. “The fastest CMEs with the strongest magnetic fields tend to occur from solar maximum into the declining phase—often one to two years before minimum.”

There’s also an intriguing pattern tied to the Sun’s magnetic polarity. Studies have found that in odd‑numbered solar cycles—like the current Solar Cycle 25—extreme storms tend to occur later in the active phase.

On top of that, the declining phase often features more coronal holes and high‑speed streams for CMEs to interact with—effectively giving eruptions a faster, more efficient path toward Earth.

“It’s like the CMEs are driving on the freeway versus inner‑city roads,” Ledvina says.

Are CMEs More Likely to Hit Earth Near Solar Minimum?

Another subtle shift as the solar cycle progresses is the latitude of sunspots themselves. Over time, sunspot activity migrates closer to the Sun’s equator—a pattern famously illustrated in the “butterfly diagram .”

“When sunspots are closer to the equator, they’re more in line with Earth,” says Ledvina. “That means any eruptions are more likely to be directed squarely at us than north or south of the ecliptic plane.”

While individual CMEs can still launch in unexpected directions, this equatorward drift makes a statistically meaningful difference over the course of the solar cycle.

What Aurora Chasers Should Expect in 2026

For aurora enthusiasts, 2026 may bring fewer geomagnetic storms overall, but according to Ledvina, the odds of a rare, extreme once-in-a-decade event are actually higher.

Space weather activity may become less frequent overall as sunspot numbers decline, Ledvina says, but coronal holes can provide a steadier rhythm of minor-to-moderate storms and visually striking auroras, particularly at high latitudes. And there’s always the possibility of a surprise.

“There is the odd chance of a surge in solar activity and sunspots which could create a surge of space weather and potential extreme events,” he notes. “Kind of like what we saw with the November 11–12, 2025, geomagnetic storm and the recent G4 storm earlier in January, which had one of the strongest magnetic fields in CME ever recorded at Earth.”

In other words, while the Sun may be calming down, it’s far from quiet—and for aurora watchers in 2026, that could still mean plenty of nights worth watching the sky.